Medical disclaimer: This article is for general education only and is not personal medical advice. Do not start, stop, or change prescription medications without your clinician. If you think you’re having a medical emergency, call your local emergency number.

Pharmacology has two big halves: pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD). PK is “what your body does to the drug.” PD is “what the drug does to your body.”1,2

This section is a PK primer you can actually use: why the same medication can feel “strong” for one person and “ineffective” for another, why route of administration changes everything, and the importance of things like liver enzymes, kidney function, and interactions.

PK is essentially the logistics department of medicine. The drug has a destination. The body has customs, toll roads, and a very motivated cleanup crew.1,2

Basics of pharmacokinetics I (absorption, bioavailability, distribution, metabolism, half-life)

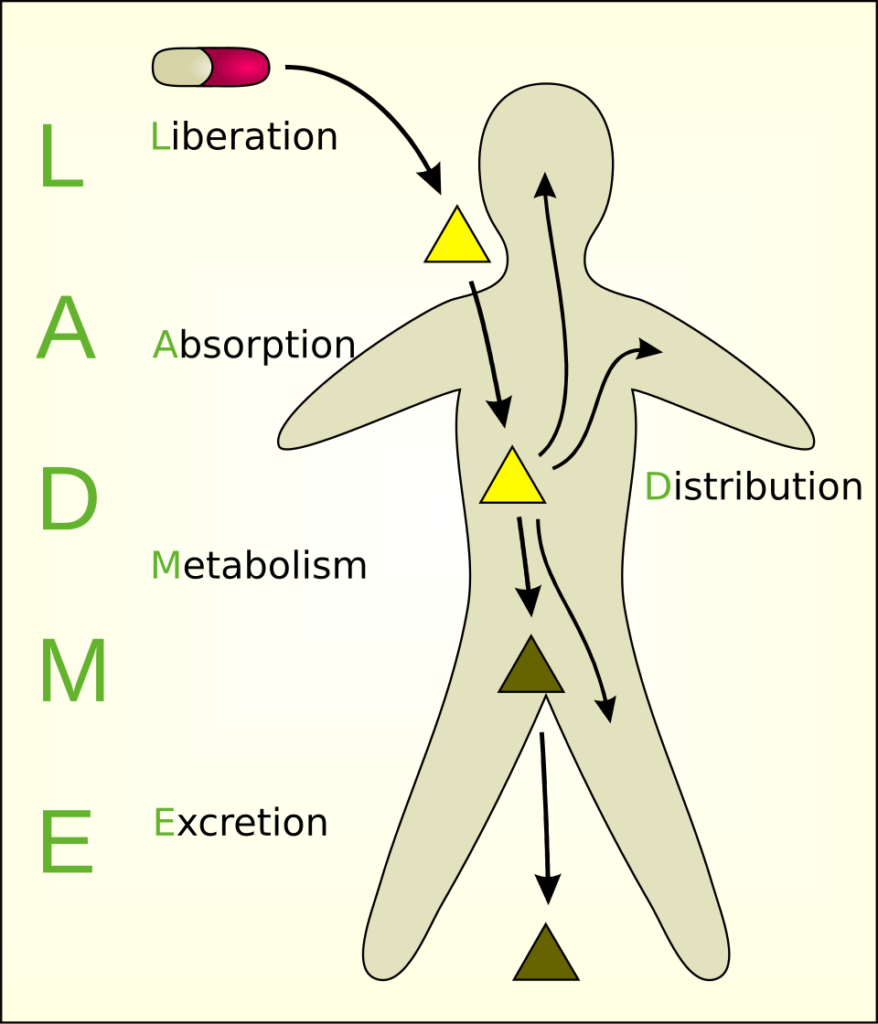

PK is often summarized as ADME: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion.1,2 If you never memorize another acronym again, ADME is critical to pharmacokinetics.

1) “Dose” is not the same as “exposure”

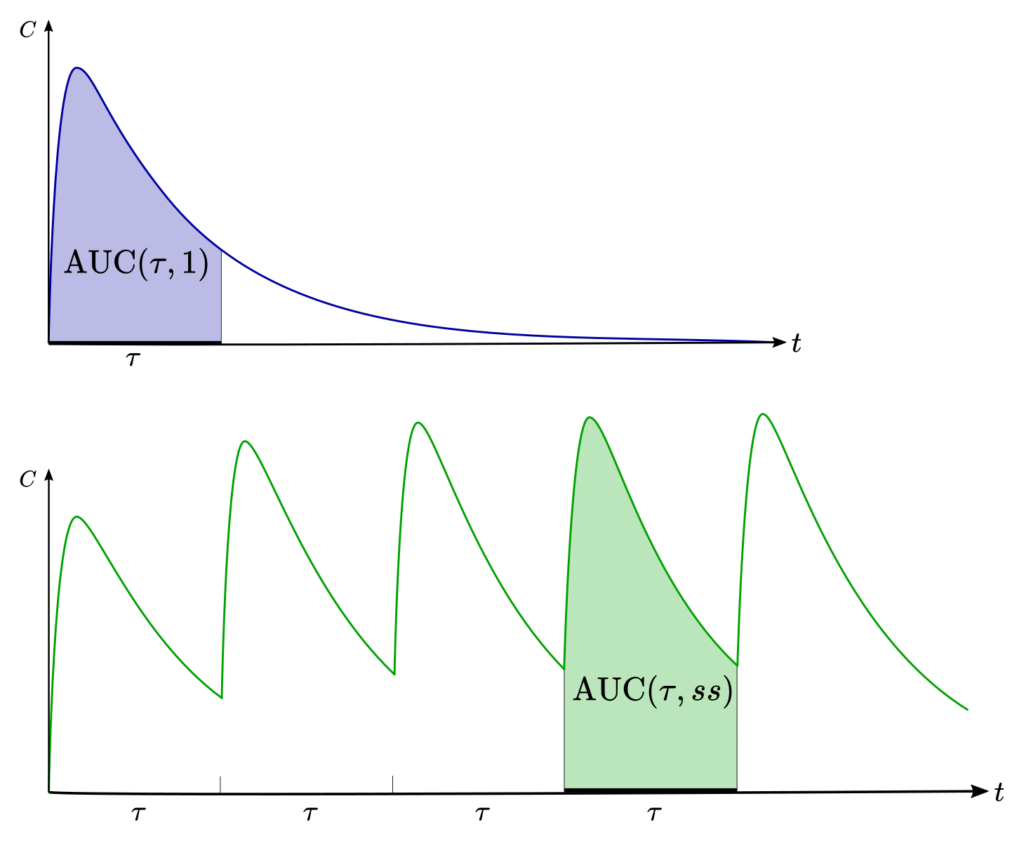

When you swallow 500 mg of a drug, you did not “get” 500 mg of drug into your bloodstream. What matters clinically is exposure: how much drug shows up in the blood over time, and how long it stays there.2,3

Pharmacokineticists quantify exposure using the concentration-time curve. The area under that curve (AUC) is the classic shorthand for “total exposure.”2 Picture a hill on a graph: higher hill = more exposure; wider hill = longer exposure.

2) Bioavailability: how much survives the trip into the bloodstream

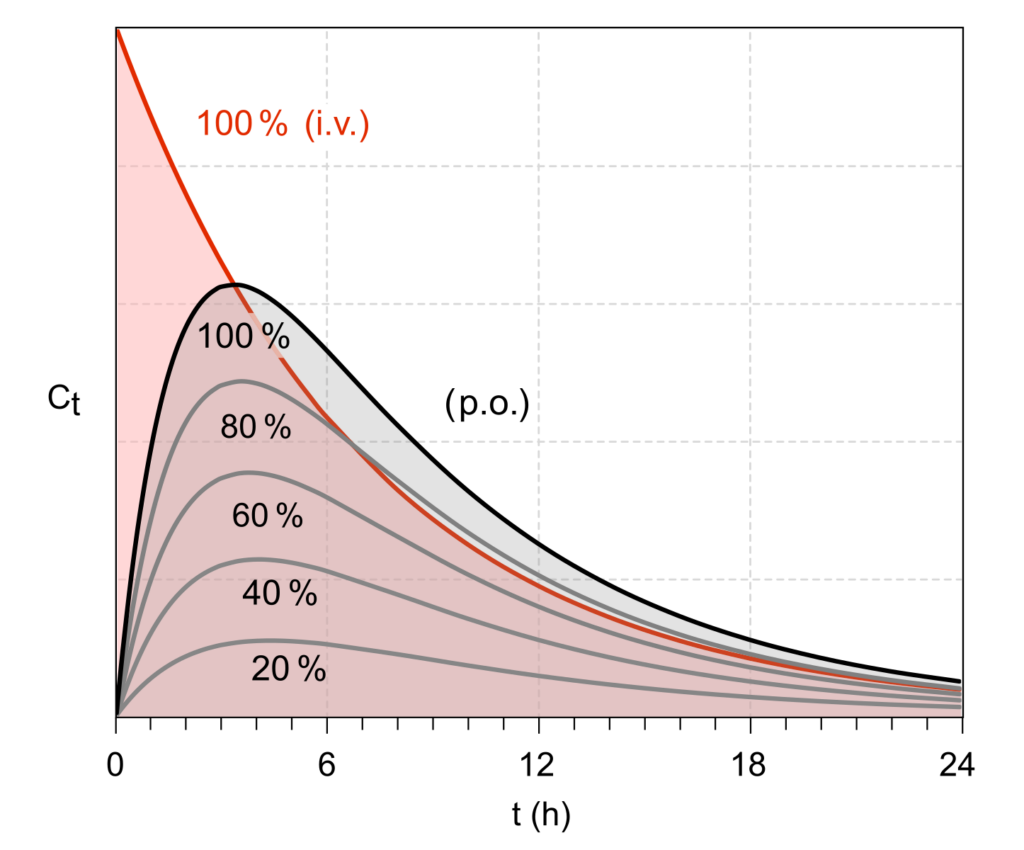

Bioavailability is the fraction of an administered dose that reaches systemic circulation (your “main bloodstream”) unchanged.1,3 Intravenous (IV) dosing is defined as 100% bioavailable because it starts in the bloodstream by definition.1,3

Oral dosing (by mouth, often written as PO for “per os”) typically has lower bioavailability because a drug can be degraded, poorly absorbed, or metabolized before it ever reaches the systemic circulation.1,3

Simple visual: imagine mailing a package. IV is handing it directly to the recipient. Oral is sending it through a postal system that includes rainstorms, customs, and a dog that hates cardboard. Bioavailability is what arrives intact.

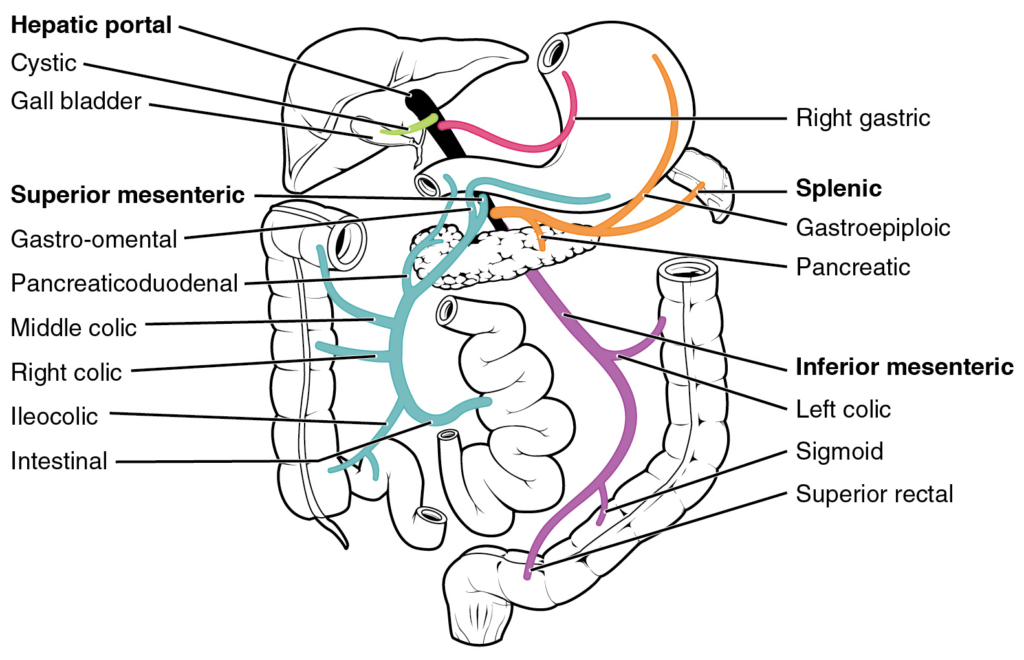

3) First-pass effect: the gut-liver “toll booth”

Many oral drugs are absorbed from the gut into the portal circulation, which routes blood straight to the liver before it joins the rest of the body. The liver (and sometimes the gut wall itself) can metabolize a large fraction on this first pass, lowering bioavailability.4

This is why some medications are designed for non-swallowed routes. A classic example is nitroglycerin (Nitrostat): it’s used sublingually (under the tongue) for rapid effect and to bypass substantial first-pass metabolism.3,4

First-pass isn’t “bad.” It’s just a reality. Sometimes it protects you. Sometimes it makes a pill feel mysteriously weak. Either way, the route you choose determines whether you pay that toll booth.1,4

4) Molecular structure quietly predicts what pills can do

Before a drug is ever tested in humans, chemists make educated guesses about oral absorption by looking at the molecule’s physical properties (size, flexibility, hydrogen bonding, polarity). There are well-known “rules of thumb” showing that highly flexible molecules with lots of hydrogen-bonding capacity tend to struggle with oral bioavailability.5

This is not magic; it’s physics. If a molecule is too polar and “sticky” with water, it may have trouble slipping through the lipid membranes that line the gut wall. If it’s too large or too floppy, it may also have trouble crossing efficiently.5

Some molecules were just never going to be great pills no matter how much we believe in them.

5) Distribution: where the drug goes after it reaches the blood

Once a drug is in systemic circulation, it doesn’t politely remain in the blood. It distributes into tissues based on blood flow, binding, permeability, and the drug’s affinity for tissue components.1,2

Two patients can have the same blood level but different effects if the drug distributes differently to the “effect site” (like the brain, lung tissue, or inflamed joints). Distribution is why location matters, not just amount.1

6) Volume of distribution: the “where is it hiding?” number

Volume of distribution (Vd) is an apparent volume that describes how extensively a drug leaves the bloodstream and enters tissues.9 A high Vd usually means the drug is largely in tissues rather than in plasma; a low Vd suggests it’s mostly staying in the blood compartment.1,9

Useful mental picture: your bloodstream is a lobby. Some drugs linger in the lobby. Others wander deep into the building. Vd is the estimate of how much building the drug is occupying.

Vd is also why “blood level” can be a misleading comfort blanket for some drugs. A drug can be doing a lot in tissues even if the plasma concentration looks modest.1,9

7) Protein binding: the “free drug” concept

In blood, many drugs bind to proteins (often albumin). Only the unbound (“free”) fraction can typically cross membranes and interact with targets.1 This is why changes in protein binding (from illness, age, or interactions) can matter for certain medications—especially drugs with narrow therapeutic windows.1

Practical example (no numbers needed): if a drug is highly protein-bound, small shifts in binding can change the free fraction more than you’d expect. That’s one reason we care about interactions and liver disease in patients on certain high-risk meds.1

8) The blood-brain barrier: your brain’s “airport security”

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts many molecules from entering the central nervous system. Beyond simple fat-solubility, the BBB uses transporters—like P-glycoprotein (P-gp)—that actively pump certain drugs back out of the brain.11

Clinically, this shows up in familiar ways. First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) tend to be sedating because they enter the brain more readily. Many second-generation antihistamines were designed (in part) to minimize brain penetration, and P-gp plays a role in keeping some of them out.11

Visual descriptor: crossing into the brain isn’t just about having the right “shape.” You also need to avoid getting escorted out by molecular bouncers.

9) Metabolism: Phase I, Phase II, and “chemistry” of the liver

Metabolism generally means enzymatic transformation of a compound—often to make it easier to eliminate. Enzymes are biological molecules that “catalyze” or speed up reactions. Phase I reactions (commonly oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis) frequently involve cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.6 Phase II reactions often attach a group (like glucuronide or sulfate) that increases water solubility and facilitates excretion.1

Memorizing the organic chemistry of these reactions is less important than knowing their impact. Some medications will be completely deactivated after one reaction where as others will have “active metabolites” meaning that their byproducts have their own, often unique drug effect.

CYP enzymes are central to drug-drug interactions. Some medications inhibit CYP enzymes (slowing metabolism of certain drugs), while others induce them (speeding metabolism).7 This is one of the reasons “med list accuracy” is not administrative busywork, but essential to pharmacokinetics.

Grapefruit is a famous example: grapefruit products can alter the metabolism or transport of certain drugs in a way that meaningfully changes drug exposure for some medications.12 Not every drug interacts, and it’s not a class-wide effect—this is very drug-specific—but it’s a clean illustration of how food can change PK.12

10) Prodrugs: when metabolism is the point

Some medications are intentionally designed as prodrugs: they’re relatively inactive until the body converts them into the active form. Think intentional active metabolites. This strategy can improve absorption, distribution, stability, or targeting.8

In plain terms: sometimes the “toll booth” is used as a feature, not a bug.

11) Half-life: how quickly drug levels decline

Elimination half-life is the time it takes for the drug concentration to drop by about 50% (under first-order kinetics, which is common in clinical practice).10 Half-life connects to two other pillars: clearance (how efficiently the body removes the drug) and volume of distribution (how widely it spreads). For many drugs, t1/2 is approximately 0.693 × Vd / clearance.10

Simple math that’s genuinely useful: steady state (the “plateau” level during regular dosing) is typically reached after about 4 to 5 half-lives.10 Likewise, most of a drug is effectively eliminated after about 4 to 5 half-lives once you stop it.10

Example with pretend numbers: if a medication’s half-life is 12 hours, you’d expect it to approach steady state in roughly 2 to 3 days (48–60 hours). If the half-life is 2 days, steady state can take about 8–10 days. Same drug class, totally different timeline.

One nuance that matters clinically: “half-life” in plasma is not always the same thing as “duration of effect” in tissue. A drug can linger at the receptor site, have active metabolites, or trigger downstream changes that last beyond the blood level curve.1,2

12) Why we ask about kidneys, liver, and “everything you take”

Clearance often depends heavily on the liver and kidneys. Impairment in either system can change drug exposure, half-life, and side-effect risk.1,10 Add drug-drug interactions (CYP inhibition/induction), and it becomes obvious why medication management is a whole discipline and not guesswork.7

Basics of pharmacokinetics part II (alternative routes of administration)

Sometimes a pill isn’t the best delivery method. Reasons include poor oral bioavailability, heavy first-pass metabolism, the need for rapid onset, GI intolerance, or a goal of more stable blood levels.1,3

Route of administration is not a minor detail. It can change peak level (how high), time-to-peak (how fast), total exposure (AUC), and side effects.1,2

1) Sublingual and buccal: absorption through the mouth

Sublingual (under the tongue) and buccal (between cheek and gum) routes can partially bypass first-pass metabolism by absorbing drug into venous drainage that reaches systemic circulation more directly.3,4

Common example: nitroglycerin (Nitrostat) is used sublingually for rapid onset and to avoid being inactivated before it can work.3,4

Real-world limitation: some portion is often still swallowed, and absorption can be slower or variable depending on formulation and saliva flow.3

2) Transdermal: slow and steady through the skin

Transdermal patches deliver drug across the skin over hours to days. This route can provide smoother levels and avoid first-pass metabolism, but it works best for small, lipophilic, potent drugs (because skin is an excellent barrier).13

Common examples include nicotine (Nicoderm), certain hormone patches, and motion-sickness patches. The theme is consistent: low-dose, steady delivery, minimal GI involvement.13

Important reality: “topical” does not always mean “local only.” Some compounds go systemic even when applied to skin, which is why we still consider interactions and side effects for certain topicals.13

3) Intranasal: fast, convenient, and sometimes surprisingly powerful

The nasal route can offer rapid absorption and avoids first-pass metabolism. It’s also noninvasive, which matters for real humans living real lives.14

There’s also a special case: for some molecules and formulations, intranasal delivery may access pathways connected to the brain (via olfactory/trigeminal regions), which is one reason this route is intensely studied for CNS delivery.14

Common examples include intranasal migraine therapies and emergency formulations like intranasal glucagon (Baqsimi). The larger concept is what matters: nasal delivery is often chosen when speed and practicality are priorities and when oral delivery is unreliable or too slow.14,15

Limitations: nasal dosing is constrained by volume, formulation, mucosal irritation, congestion, and (when using multiple sprays) the simple physics of limited surface area and runoff.14,15

4) Inhaled: huge surface area, fast absorption (often local effect)

The lungs have an enormous surface area and thin barriers, which can allow rapid drug absorption. Many inhaled medications are designed for local effect in the airways (like albuterol [Ventolin]) rather than systemic exposure, but systemic effects can still occur depending on the drug and dose.1

5) Injectable: predictable exposure, but more invasive

Injectable routes include IV (into a vein), IM (into muscle), and SC (subcutaneous, under the skin). These routes generally provide higher and more predictable bioavailability than oral dosing and can be used when rapid onset is required or when GI absorption is unreliable.1,3

Common examples include vaccines (often IM), insulin (multiple formulations, often SC), and many modern metabolic therapies such as semaglutide (Ozempic) administered SC. The tradeoff is practical: injections can be inconvenient, uncomfortable, and require technique and supplies, which is why drug delivery innovation is relentless.1,13

Bottom line

Pharmacokinetics explains why the label dose is not the full story. What matters is exposure (how much reaches circulation and target tissues, and for how long).1,2

Oral medications face absorption limits and first-pass metabolism; alternative routes can bypass some of these barriers and change onset and side-effect patterns.3,4,14

Distribution (including BBB penetration), metabolism (especially CYP enzymes), and half-life (including the “4–5 half-lives to steady state” rule) are the backbone concepts for predicting how a medication will behave in the real world.7,10,11

References

1. Derendorf H, Schmidt S. Rowland and Tozer’s Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: Concepts and Applications. 5th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

2. Ito S. Pharmacokinetics 101. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16(9):535-536. doi:10.1093/pch/16.9.535

3. Price G, Patel DA. Drug Bioavailability. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Updated July 30, 2023. Accessed January 4, 2026.

4. Herman TF, Santos C. First-Pass Effect. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Updated November 3, 2023. Accessed January 4, 2026.

5. Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem. 2002;45(12):2615-2623. doi:10.1021/jm020017n

6. Zhao M, Ma J, Li M, et al. Cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug metabolism in humans. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(23):12808. doi:10.3390/ijms222312808

7. Hakkola J, Hukkanen J, Turpeinen M, Pelkonen O. Inhibition and induction of CYP enzymes in humans: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94(11):3671-3722. doi:10.1007/s00204-020-02936-7

8. Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, et al. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(3):255-270. doi:10.1038/nrd2468

9. Mansoor A, Mahabadi N. Volume of Distribution. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Last Update: July 24, 2023. Accessed January 4, 2026.

10. Hallare J, Gerriets V. Elimination Half-Life of Drugs. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Updated May 3, 2025. Accessed January 4, 2026.

11. Chen C, Hanson E, Watson JW, Lee JS. P-glycoprotein limits the brain penetration of nonsedating but not sedating H1-antagonists. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(3):312-318. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.3.312

12. Bailey DG, Dresser G, Arnold JMO. Grapefruit-medication interactions: forbidden fruit or avoidable consequences? CMAJ. 2013;185(4):309-316. doi:10.1503/cmaj.120951

13. Prausnitz MR, Langer R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(11):1261-1268. doi:10.1038/nbt.1504

14. Illum L. Nasal drug delivery—possibilities, problems and solutions. J Control Release. 2003;87(1-3):187-198. doi:10.1016/S0168-3659(02)00363-2.

15. Costantino HR, Illum L, Brandt G, Johnson PH, Quay SC. Intranasal delivery: physicochemical and therapeutic aspects. Int J Pharm. 2007;337(1-2):1-24. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.03.025.

No responses yet